What do you do when you’re not punk enough for the punks, and not gay enough for the gays? You start your own club.

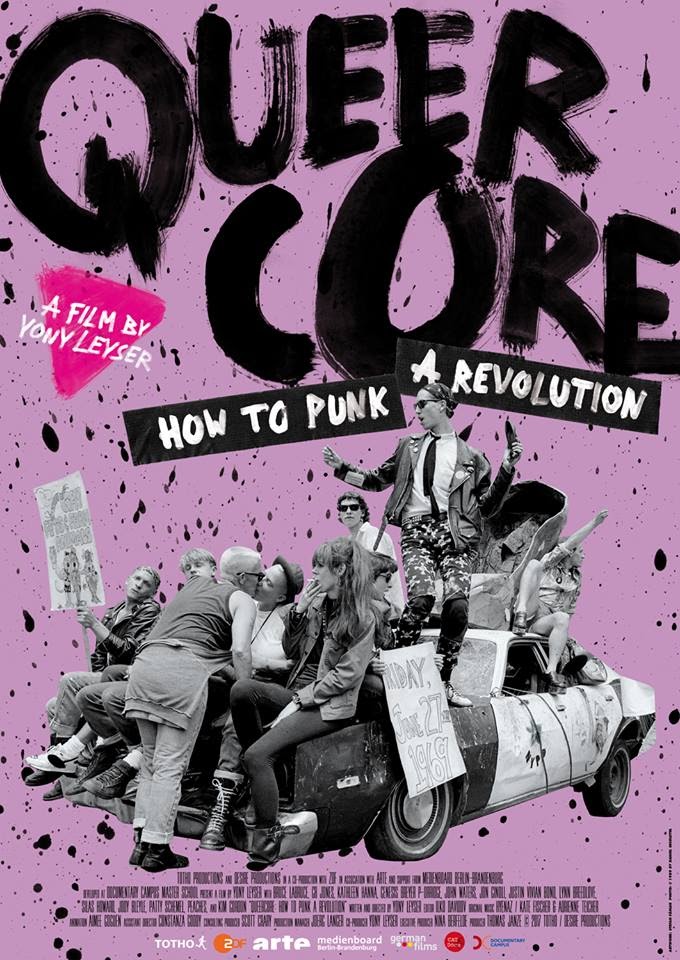

That’s the story behind the 2017 documentary Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution, directed by Yony Leyser. Beginning in the mid- to late-80s and continuing through to the 1990s, Queercore tells the story of how a few people, feeling outcast within their communities, decided to take matters into their own hands. It started almost simultaneously in both Toronto, Canada, and parts of California, where artists like G.B. Jones and Bruce La Bruce began creating short films, art, music, and zines that reflected their realities in society.

As part of the queer community, they felt they didn’t relate to the extravagance of the “bourgeoisie” they experienced at gay clubs, and they were disturbed by the segregation they were witnessing between gay men and lesbians at the time. They felt much more comfortable going to a punk show to hear some good music. But in the punk world, the vibe dripped with exaggerated machismo and neo-nazi themes, which didn’t always feel so welcoming to queer people.

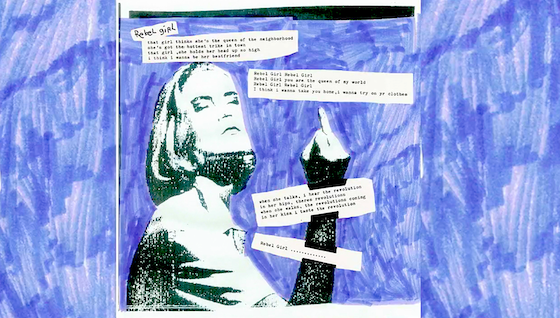

So, in true DIY Punk fashion, they began creating the world that they wanted to see, in the form of films, visual art, and an original handmade zine (a photocopied mini-magazine full of text, images, and collages) called J.D.’s. In the zine, they compiled photos, drawings, and text that featured stereotypical-looking punk characters combined with graphic homoerotic imagery and queer themes. They featured articles on punk bands who sang about gay sex and radical politics of rejecting mainstream assimilation, like the all-girl post-punk band that G.B. Jones was in at the time, Fifth Column.

They began distributing their art and zines at shows and events, all the while implying that they had already established a huge international “Homocore” movement for others to join. As Bruce La Bruce says in the film: “Our strategy was to pretend that Toronto had a full-fledged crazy gay punk scene already happening.”

And it worked. The movement did grow, as queer punk zines started popping up in California and the Pacific Northwest, and the 90s brought bands like Pansy Division (who toured with Green Day) and Tribe 8, who started playing rock music from an openly queer perspective. Tribe 8 was an all-female band that pushed the envelope even further by only allowing self-proclaimed “dykes” in their group (rejecting the more widely accepted “lesbian” label), with a lead singer, Lynn Breedlove, who sang her snarky, angsty songs with no shirt on, and even wore a strap-on dildo on stage that straight guys would come up and give blow jobs during the show (which is gratuitously shown in the film).

Breedlove speaks in the documentary of how they were just ready to take feminist theory and lesbian activism to a new level. “Lesbians were pissed at us. They were like ‘You’re stomping around on all this work we’ve done.'” But she says they just took the ideologies to the next level by building on what had already been established. Feminists before her had claimed that women were in charge of their bodies, and she wanted to prove it by singing bare-chested and playing with rubber dildos on stage. She says it was a clapback at feminists who had espoused radical theories, but were still too complacent by assimilating into the dominant culture. She justifies her actions in typical punk defiance by retorting in the film: “You said I’m in charge of my body, right? That’s what you said, Mom.”

The early- to mid-1990s saw the punk rock feminism movement go even further, to include themes of female empowerment and address issues like rape culture and incest, while creating safe spaces for girls in the music scene. Bands such as Bikini Kill and Bratmobile launched a “RiotGrrrl” revolution with the same DIY mentality that Queercore had used in its beginnings. Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of Bikini Kill, which was formed in Olympia, Washington, talks in this documentary about an interview she did with L.A. Weekly when RiotGrrrl was starting. She explained how the movement sparked from small groups of musicians, writers, and artists in Washington state and Washington D.C. to become a nationwide wave of girl power:

“We had just had like two meetings in D.C. And [in the interview] I said, ‘Oh, yeah, RiotGrrrl is like all over the country. There’s meetings happening everywhere…Minneapolis, Chicago, L.A…’ I just made up a bunch of places. Girls started looking for meetings. I said ‘It’s totally a phenomenon.’ And then it became a phenomenon, because I said it was.”

Hanna says she was greatly influenced by G.B. Jones and J.D.’s to create her own culture and distribute her own zines, to spread the word on how women could support each other in their communities. Hanna collaborated with other female artists at the time to publish zines that promoted female bands, provided resources for substance abuse and sexual abuse, and gave a space for women in the punk world to highlight their art, music, poetry, and stories. Girls at punk shows who were reading the zines and screaming along to the “Girl Style Revolution Now” lyrics started feeling empowered to do the same in their own cities and towns, and the mentality spread.

By the mid-1990s, there was an eruption of bands who were producing original Queercore and RiotGrrrl music, like Team Dresch, The Frumpies, 7 Year Bitch, Extra Fancy and others. But as quickly as the fire started, it already began to burn out by the end of the decade. Many physical zines started fading away, as the Internet started to emerge into daily life, and online live journals and blogs became the new outlets of expression. Punk became more pop, and as some of those interviewed in this documentary lamented, “Girl Power” became largely commoditized with groups like the Spice Girls.

The movement lost its momentum toward the end of the 90s, but many bands that followed afterward did take on the mantle of Queercore artistic expression, like Peaches and Gossip, who started using more electronic and pop sounds to carry the message. And though the original days of Homocore and RiotGrrrl may be over, many of the bands are still making records, and are even reuniting to tour again, as Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney recently started to do before the pandemic halted live shows.

The Queercore documentary takes viewers through both familiar and uncharted territory within the punk world, while introducing fans to scores of bands they can jot down to start listening to their back catalogs. The DIY ethic portrayed by the documentary’s queer-punk trailblazers is at once awe-inspiring and motivating, especially in current times of quarantine forcing society to find more paths to self-sufficiency. This film is a must-see for any true fan of the punk genre, and a musical salve for those who still feel like they just don’t fit in.

Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution is available to watch streaming for free on TubiTV.com.